Grotto Point (Sydney, Australia)

Given the current health crisis that is taking place around the world, in the past few months I haven't had the chance to explore archaeological sites around Sydney. With social distancing restrictions easing at the moment, together with the surprisingly mild June weather, the last few weekends have provided a nice opportunity to venture back out into nature. After almost two months of being primarily confined to home, Completing Sydney and I headed out to the Spit Bridge to Manly coastal walk, which starts in the northern beaches suburb of Clontarf. The 10km path hugs the coast and weaves through bushland, opening up into small beaches and covering areas of the northern section of the Sydney Harbour National Park where visitors are given panoramic views of the surrounding area and ocean.

|

| National Parks NSW |

In addition to these views, there are a few points of cultural heritage of the Cammeraygal people, the local inhabitants of this area, along the walk. The Cammeraygal people are the traditional custodians of the land north of Sydney Harbour, stretching from North Sydney to Manly, and occupied this region for at least 5800 years. Other notable Cammeraygal sites include the Coal Loader Site at Balls Head in Waverton. The below map of Sydney Harbour and Cammeraygal land was created by a colonial ship's captain in 1788, with Balls Head in the top left.

The name Cammeraygal was ascribed to these people on the basis of one of

their leaders, named Cammerragal, whose presence was recorded by the

colonial settlers. Such settlers also recorded words spoken by the local

peoples in this region, providing written records (now stored at the

State Library of NSW) of some of the vocabulary that has since been lost

due to the devastating cultural impacts of colonisation. Barangaroo, the second wife of Bennelong (a key interlocutor between the local peoples of Sydney and the colonisers), was of the Cammeraygal people and the area of the Sydney city west of The Rocks is named after her. It is important to keep the knowledge and stories of the first peoples of Sydney in mind when exploring our city.

The first point of significance in the Spit to Manly walk is quite close to the beginning of the path, near the Spit Bridge. Here, Google Maps identifies an Indigenous cave shelter, nestled into the walking path.

There is only very minimal information available about this shelter, but its capacity to protect passerby from the elements is clear. From inside, there is a view over Fisher Bay.

Nearby, a small sign marks the presence of a shell midden, although its remnants are no longer easily visible. A midden is a mound of materials discarded by humans, containing shells,

bones and charcoal, that have been left behind and accumulated over time throughout generations of

occupation. A few small shells are scattered around the large rocks here, providing an indication of the vast amounts of shellfish that were gathered by the local people as a major food source. This is just one of many middens scattered across the coastal areas of Sydney that give archaeological evidence of the subsistence systems of Australia's first peoples.

Further along the walk, almost halfway through, where the Castle Rock track we were taking meets the Grotto Point track, is another track branching south. Following this steeper and less accessible track takes you to the Grotto Point Lighthouse, proposed in 1910 by the mariner Maurice Festu. Together with the Parriwi Lighthouse in Middle Harbour, Mosman, these two lighthouses provided safe passage for ships travelling to the bay. The architectural style of the lighthouse is sometimes colloquially referred to as the "Disney castle". Initially the light was lit by gas generated on site, then by compressed gas cylinders brought by boat, and eventually electricity was connected.

Shortly after joining back to the Grotto Point Track, a raised walkway leads to another point of cultural significance, the Grotto Point engravings.

Here, is a large rock platform where you can see etched engravings of a number of animals, some of which are protected by a wood barrier. There are also engravings that are outside of these barriers and can be seen by a careful eye.

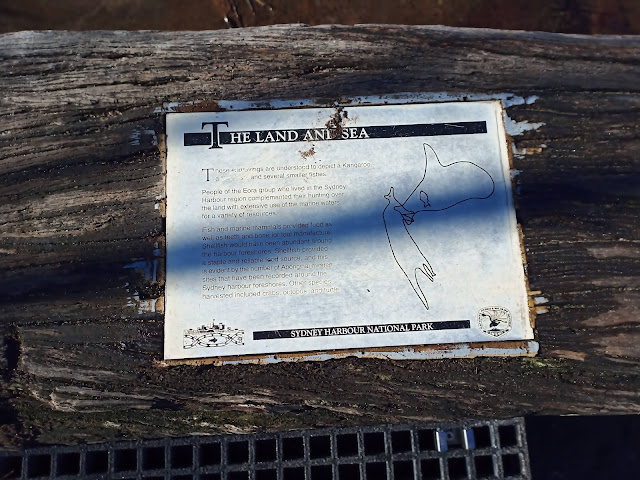

The engravings within the barriers depict a whale, a fish and a kangaroo, which can be seen more clearly in the image on the sign below. These engravings have been dated to at least 1000 years ago, and were made using tools of quartz and other hard stones in a technique where holes were carved to outline the engraving, and then these punctures were connected to one another using lines. There are many similar rock engravings across the northern region of Sydney, testament to the tens of thousands of years of occupation by Indigenous Australians.

Engravings such as these played key roles in learning, ceremonial life, storytelling and practices of intergenerational knowledge. Unfortunately much of this is knowledge no longer available to us due to the cataclysmic impact of the systematic and intentional oppression of Indigenous Australians by the European colonisers. The impacts of this subjugation are still very prevalent today and there remains significant structural changes to be made to the current situation in Australia, which is the legacy of these colonial systems. Widespread public support of this need for change is highlighted by the recent Australian Black Lives Matter protests.

Nearby, there are also signs of the many people that have visited the site in recent history, with modern engravings also carved into the rocks in this area. Although separate from the more historically significant Indigenous carvings (and a practice that should not be condoned due to the alteration and destruction of Aboriginal cultural heritage), these modern etchings are a reminder that history is continually evolving. In Sydney today, we see a community that is an amalgamation of the descendants of Indigenous Australians and colonisers, as well are more recent migrants from across the globe.

From here, after taking in the carvings, we continued on the Grotto Point Track, passing through the highest point of the Spit to Manly walk with views of the surrounding bushland and beyond. Areas of bushland like that below were managed by the Indigenous people of this area through use of fire called 'firestick farming' to manage vegetation in order avoid uncontrollable wildfire in the summer. Walking along the track today the effects of the catastrophic bushfires in late 2019/ early 2020 are still evident in the remnants of foliage.

To follow the rest of the walk, head to Completing Sydney's post on Clontarf.

Comments

Post a Comment